El audiovariómetro: el compañero indispensable de los parapentistas

Principiantes, intermedios, pilotos experimentados, competidores, pilotos biplaza: todos quieren permanecer en el aire el mayor tiempo posible (¡incluso los acróbatas!). Esta es la función principal del variómetro: indicar la velocidad vertical (en metros por segundo en el mundo del parapente, en pies por minuto en la aeronáutica).

Esta indicación de la tasa de ascenso (valores positivos) ayuda al piloto a encontrar los ascensos, y a rodarlos mejor, pero también a "flotar" mejor y desplazarse por la masa de aire, para perder el mínimo de altitud, manteniéndose en torno a la mejor tasa de ascenso posible.

Por último, la tasa de caída (valores negativos) mide la velocidad de descenso "hacia abajo". Si es demasiado alta, significa que la masa de aire no es favorable en ese punto, por lo que es necesario salir de esa zona buscando una ruta mejor y/o acelerando.

¿Por qué volar con un vario?

Para el ser humano, volar no es, por supuesto, algo natural y no tiene un sentido específico de evolución en 3D. En cuanto se pierde la referencia visual del suelo, es muy difícil saber si se está subiendo o bajando.

Sin embargo, en el asiento caliente, tengo una buena sensación cuando entro o salgo de un ascensor.

De hecho, nuestro cerebro utiliza tres sentidos para saber si nos movemos o no: el oído interno, la propiocepción y, por último, la vista.

A continuación, el cerebro mezcla estas 3 informaciones con precisión para saber dónde estás en el espacio, en qué movimiento de rotación y con qué aceleración.

Por desgracia, carecemos de información "absoluta" sobre la velocidad: es imposible saber a qué velocidad va un avión o un tren si la cortina está bajada.

Incluso nuestros sentidos pueden engañarnos, por ejemplo: cuando estamos en un tren de alta velocidad en una estación y el tren de al lado arranca, nos confundimos, y a nuestro cerebro le cuesta saber si realmente nos estamos moviendo o no hasta que giramos la cabeza para ver el andén de la estación al otro lado.

Cuando estás en una térmica establecida, no hay aceleración aunque sigas subiendo, y si estás lejos del terreno, sin una referencia visual, es muy difícil saber si estás realmente en la térmica.

El variómetro nos da esta información que nos falta y la respuesta es inmediata, ¡sabemos si estamos subiendo o bajando, y a qué velocidad!

¿Cómo funciona un vario?

Como se ha visto anteriormente, para situarse en el espacio, el cuerpo humano dispone naturalmente de "3 sensores":

- un giroscopio : el oído interno, que permite seguir la rotación (sobre 3 ejes).

- un acelerómetro : nuestra piel en contacto con el suelo, el asiento del coche, el arnés, etc., lo que nos permite seguir las aceleraciones (horizontal, vertical).

- una referencia visual : La vista, que se aferra a los marcadores horizontales y verticales para dar una referencia absoluta a los dos sentidos anteriores.

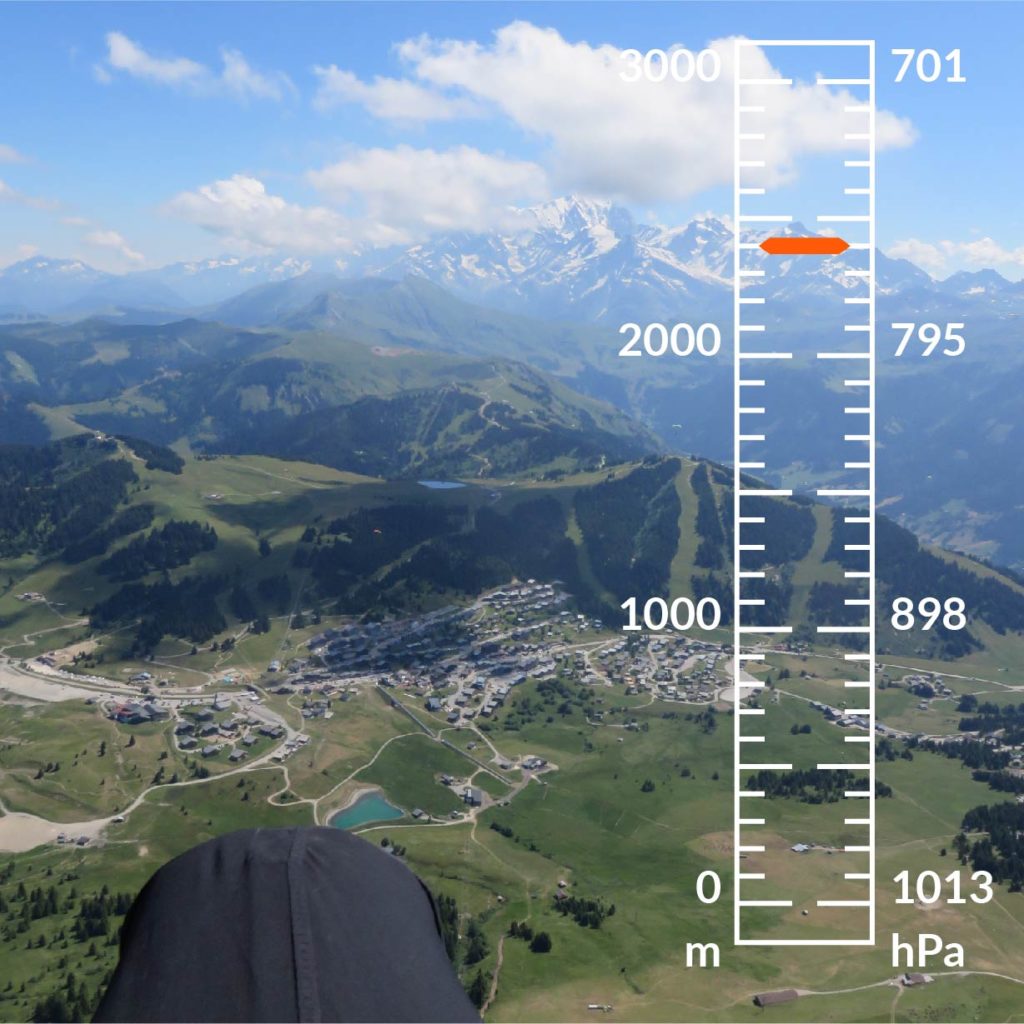

Por desgracia, carecemos de un sentido esencial para determinar la altitud: una regla vertical virtual graduada en metros, por ejemplo.

Esta información ausente pero presente es la presión. En efecto, la presión está directamente correlacionada con la altitud. Un sensor de presión permite ver la disminución de la presión a medida que aumenta la altitud.

En el contexto de un variómetro para parapente, la altitud absoluta nos interesa poco, lo que nos interesa es la variación de altitud.

Así, leyendo la presión con mucha frecuencia (al menos 50 veces por segundo, hasta 100 o 200 veces por segundo en los casos más rápidos), es posible, con un tratamiento eficaz de la señal, determinar la variación de altitud, es decir, la velocidad vertical.

¿Es posible tener un vario totalmente instantáneo?

La medición de la presión por sí sola a veces puede ser insuficiente: se necesita una variación de la presión para medir una velocidad vertical, por lo que la información obtenida siempre está ligeramente retrasada.

Por eso se utiliza un sensor de aceleración para medir la aceleración (entrada en térmica) lo más rápidamente posible: es el vario instantáneo.

Por supuesto, este sensor acelerómetro es extremadamente sensible y requiere un punto de referencia absoluto: es necesaria una corrección giroscópica.

Se trata, pues, de toda una cadena de mediciones (acelerómetro, giroscopio, presión), medidas más de 100 veces por segundo con un sofisticado algoritmo, que se realiza en el aparato, y que permite devolver al piloto una información perfectamente en fase con sus sensaciones.

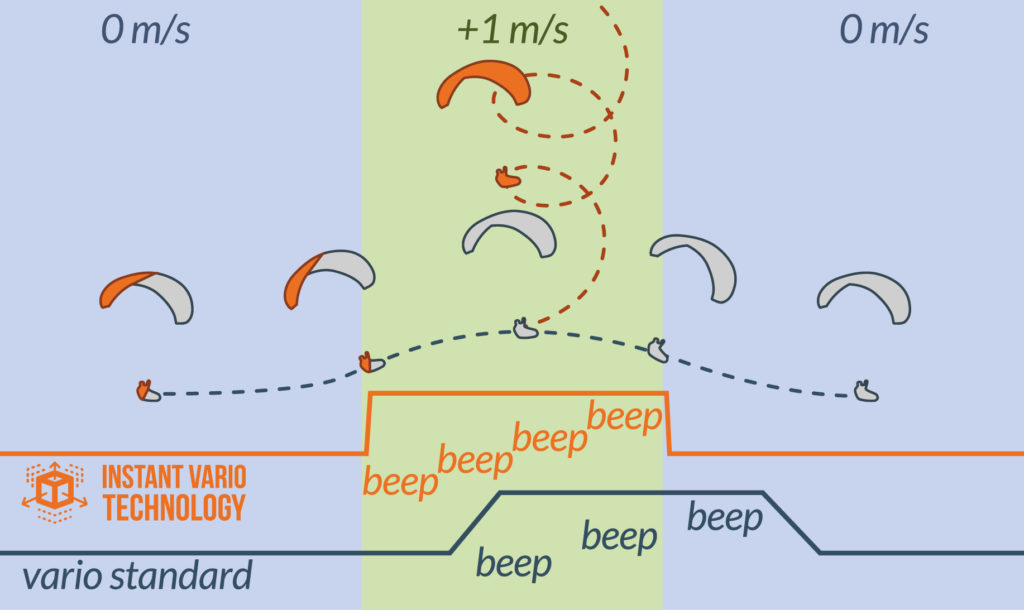

El algoritmo Tecnología Instant Vario es exclusivo de Stodeus.

Combina la información de tres sensores: acelerómetro, giroscopio y barómetro. Esto significa que el piloto obtiene una respuesta del vario "exactamente" al inicio de la térmica, y no sólo después de sentir en el arnés que "está subiendo". Lo mismo se aplica a la salida de la térmica, que es igual de importante: el vario se detiene inmediatamente al salir de la térmica.

En otras palabras, el vario está exactamente en sintonía con la sensación del piloto en el arnés. Se acabó el retraso de un segundo entre la entrada de la térmica y el inicio de los pitidos del vario.

¿Por qué un vario con sonido modulado?

Necesitamos 100% del campo visual para volar, tanto por seguridad como para ser conscientes de todo el entorno que puede ayudarnos a encontrar las térmicas.

Por lo tanto, el sentido auditivo está mucho más disponible, ya que sólo se utiliza para algunas informaciones concretas, como el arrugamiento del ala, la variación del viento relativo o una llamada de radio.

El uso del sonido (una nota) transmite información, la ausencia de sonido representa la ausencia de información.

Por tanto, es necesario modular el sonido (frecuencia vibratoria del aire) del orden de KHz, para que sea posible transmitir una información casi infinita.

Los pitidos utilizados en un variómetro de audio constan de tres parámetros:

- Frecuencia : Tono de la nota (variaciones de grave a agudo).

- Duración del ciclo : duración durante la cual se reproduce la nota y su tiempo de pausa.

- Relación cíclica : La relación entre la nota reproducida y el tiempo de pausa. Por ejemplo, un ciclo de trabajo de 50% da la mitad del tiempo reproducido y la mitad del tiempo en silencio.

Con un audio vario, nuestro sentido auditivo actúa en total complementariedad con los tres sentidos antes mencionados, y nos permite acceder instantáneamente y de forma muy precisa a la información de nuestro movimiento vertical.

Opiniones de la competencia

"No puedo imaginar volar campo a través o vivac sin el sonido del vario. Lo configuro para que sea muy comunicativo en baja sustentación seguido de una meseta en alta varios, si estoy en +7m/s sé que estoy subiendo, ¡no hace falta que me lo grites! Me gusta cuando pita inmediatamente, sin retardo, pero a veces practico sensaciones diferentes añadiendo retardo a propósito para reconocer la entrada en térmica antes de la confirmación sonora.

Además, de vez en cuando pongo el vario en silencio y practico la térmica sin vario. Es más fácil cuando estás cerca del suelo y cuando hay otros pilotos alrededor, pero a veces, especialmente cuando estás alto o en aire muy pequeño, es casi imposible. El sonido del vario hace que volar sea mucho más accesible, ya que libera nuestra atención durante la térmica, dándonos más tiempo para observar el terreno, las nubes, planificar nuestra próxima transición o simplemente admirar las vistas. Existen soluciones alimentadas por energía solar, sin limitaciones, del tamaño y peso de una pequeña caja de cerillas, así que ¿por qué no?

Al fin y al cabo, no hay muchos sonidos más magníficos que el primer pitido tras 20 minutos de laborioso rascar en el fondo de una cooma, ese sonido que luego se hace más constante y rápido y nos lleva hasta el techo".

Kinga Masztalerz, atleta del Red Bull X-Alps, voladora de vivac.

"Al principio tuve algunos problemas con la inmediatez de la respuesta de esta nueva generación de varios. En los antiguos varios solías recibir la confirmación de la burbuja térmica después de sentirla, ahora recibes la información al mismo tiempo que la sensación. Al principio es confuso, ¡pero ahora es imposible volver atrás!

Es genial saber de inmediato si realmente estás subiendo o sólo bajando menos, para poder reaccionar más rápido y rendir mejor".

Jacques Fournier (alias Grand Jack), competidor internacional.

Vario Tone Editor: la herramienta definitiva para afinar el vario

de su UltraBip

Aquí encontrará toda la información que le permitirá aprovechar todo el potencial del Vario Tone EditorLa herramienta de ajuste UltraBip vario (accesible a todos, incluso sin UltraBip).

El Vario Tone Editor también está disponible en el Configurator del GPSBip / GPSBip+ (el predecesor del UltraBip).

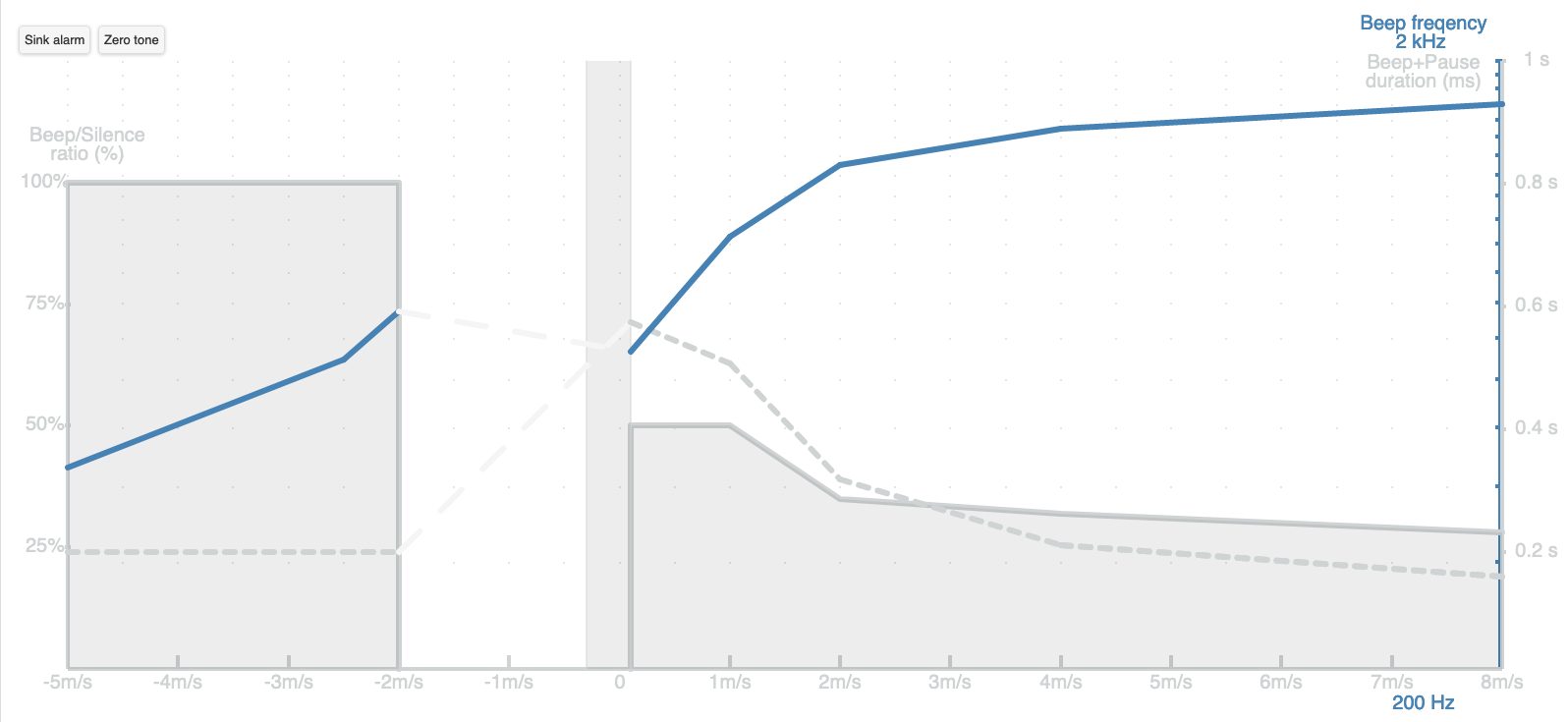

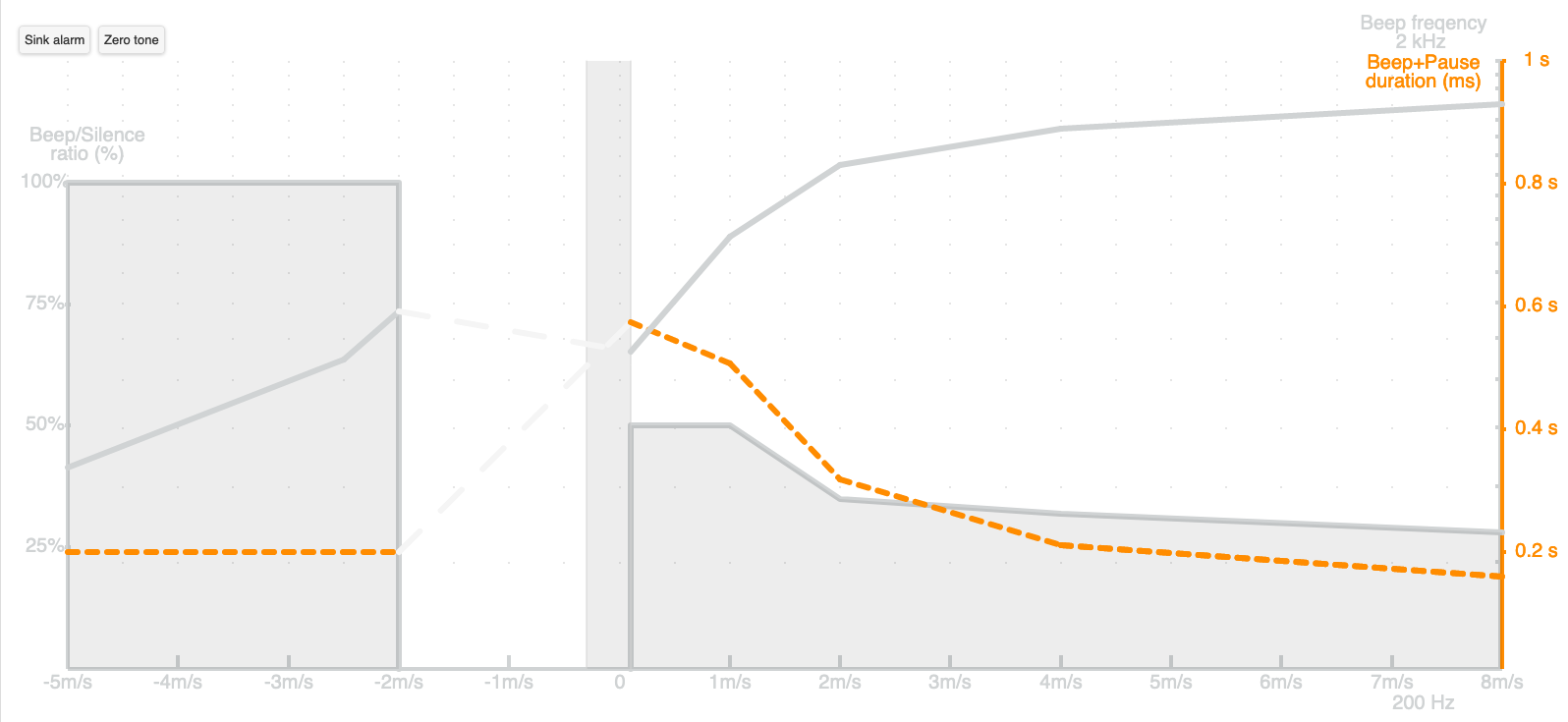

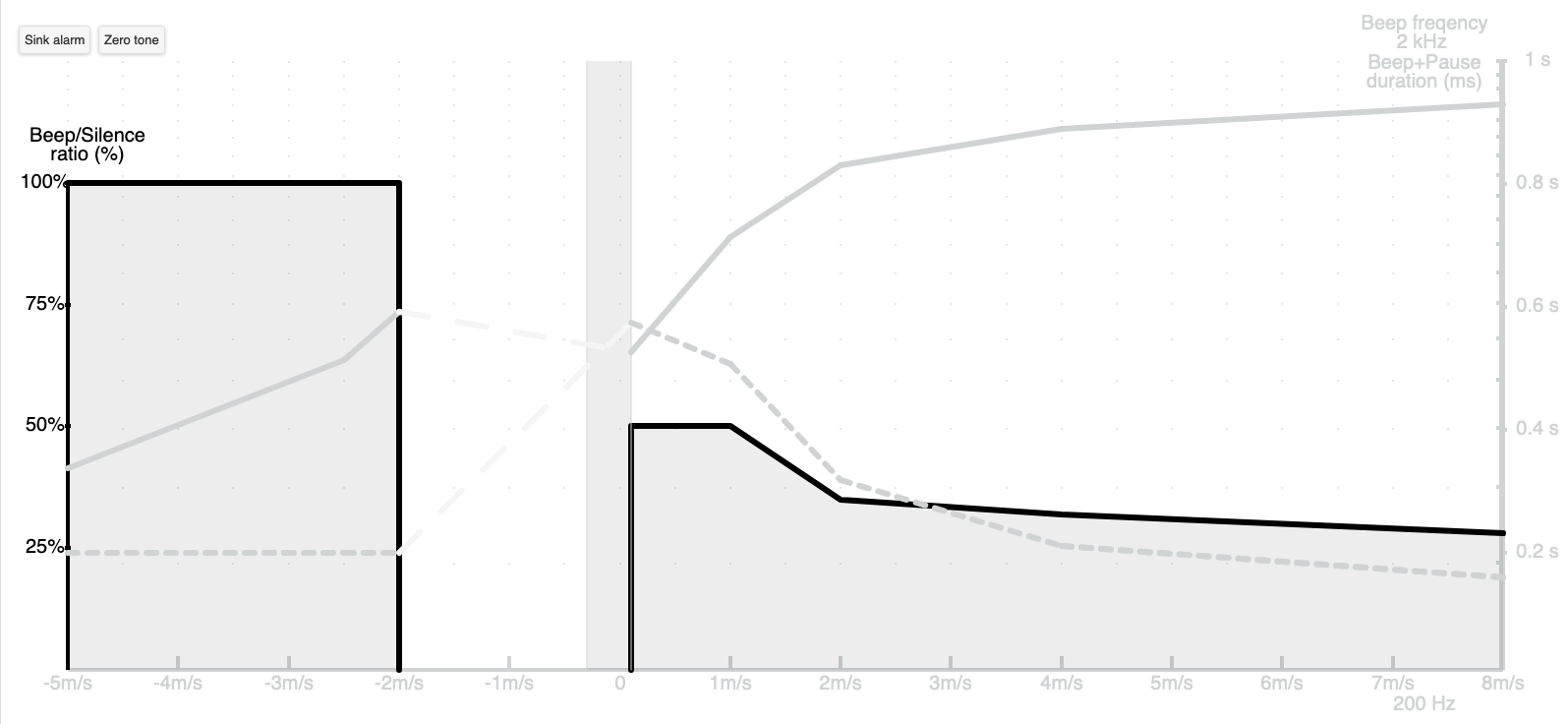

En Vario Tone Editor permite ajustar los 3 parámetros que componen el sonido, de forma gráfica e intuitiva:

Como se ha visto, hay 3 componentes esenciales:

La curva de frecuencia de pitidos :

La curva de tiempo de ciclo :

La curva del ciclo de trabajo :

¿Qué formas dar a las curvas?

Es importante adaptar el tipo de respuesta sonora en función de la velocidad de subida/bajada encontrada y del nivel de conducción.

Una respuesta lineal no nos permite aprovechar al máximo nuestro sentido auditivo. Además, es mucho más interesante tener más información en pequeñas térmicas de +0,5m/s que aumentan lentamente hacia +1m/s (ganancia de 100%) que en un monstruo de +6m/s que tira hacia +7m/s (ganancia de 15%).

Por eso, la mayoría de los varios ofrecen una curva logarítmica (a menudo los 3 parámetros, con algunas variaciones).

El Vario Tone Editor permite no sólo modificar estos 3 parámetros, sino también definir diferentes tipos de respuestas:

Respuesta rápida (ejemplo):

Respuesta amortiguada (ejemplo) :

La alarma de descenso

Tan temida como visceralmente odiada, esta función permite al piloto detectar una tasa de caída superior a la tasa de caída nominal del parapente en aire en calma (normalmente entre -0,8 y -1,7 m/s para un parapente estándar).

El objetivo es informar al piloto de que se encuentra en una masa de aire en fuerte descenso que le hará perder mucha altitud e incluso correr el riesgo de tener que aterrizar si permanece demasiado tiempo en esta zona.

Corresponde al piloto fijar el umbral correcto en función de su nivel y capacidad para manejar esta información en vuelo.

En general, un piloto principiante tenderá a desactivar esta función ya que puede percibirla como demasiado estresante, un piloto intermedio querrá una alarma de descenso en torno a -3m/s, y en general un competidor preferirá ajustarla a -2m/s, aunque eso signifique que se active en cuanto se salga de la térmica.

Puesta a cero, o detector de baja elevación

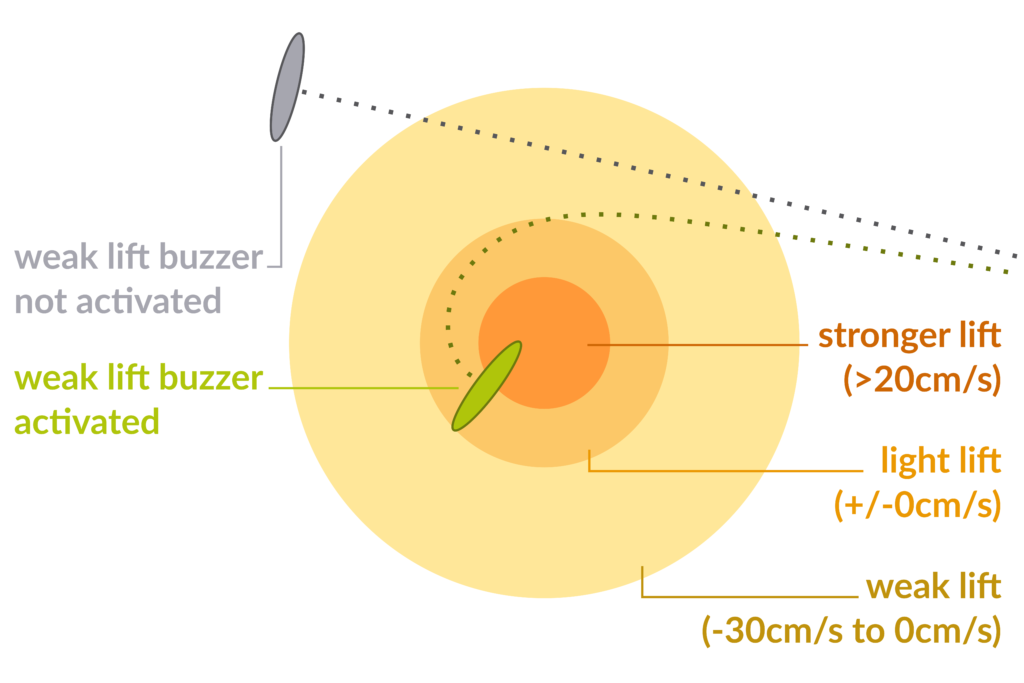

Este sonido se compone de modulaciones cortas que indican al piloto una sustentación débil (desde -30cm/s hasta su ajuste de velocidad de ascenso, por defecto +20cm/s), no lo suficientemente fuerte como para rodar, pero que le ayudará a encontrar la térmica cercana.

En la imagen, el piloto en gris no ha activado la función de puesta a cero, mientras que el piloto en verde la ha activado. Cuando llega a la zona de sustentación débil, los pitidos de puesta a cero se activan, informando al piloto de que se está acercando a una zona de sustentación débil, todavía no óptima para el enrollado, pero invitándole a permanecer atento ya que puede haber una térmica más fuerte cerca.

Volumen del sonido

Los vario son, o deberían ser siempre, ajustables con al menos 3 niveles de volumen, para adaptar mejor el volumen al uso. Cuando el vario se coloca en el casco, en un vuelo biplaza por ejemplo, el volumen mínimo permite permanecer discreto y no molestar al pasajero.

En navegación de rendimiento, o con un casco ruidoso con viento relativo, se utilizará el volumen medio.

Por último, en la cabina, en posición prona, con un casco integral, se requiere un volumen elevado.

El volumen del UltraBip (como el de todos los instrumentos STODEUS) puede ajustarse fácilmente a estos tres niveles mediante el interruptor lateral, incluso durante el vuelo.

¿Y por qué no transmitir la información de otra manera?

Otras tecnologías no visuales son posibles, como la vibración.

Pero las vibraciones, y más aún las modulaciones (variaciones) de las vibraciones, son mucho más difíciles de percibir. No es posible transmitir tanta información a través de las vibraciones como la que puede contener el sonido.

Además, pueden interferirse fácilmente. Por ejemplo, llamadas perdidas en el smartphone que vibran mientras caminas.

Por último, es una tecnología comparativamente intensiva en energía: hay que mover (o hacer vibrar) una masa (aparato, mano, cuerpo), mientras que el sonido es la vibración del aire (por definición mucho más ligero).

El piloto es el único responsable de la seguridad de sus vuelos, y STODEUS no se hace responsable de este artículo. Corresponde al piloto realizar sus propios ajustes en función de su nivel de pilotaje y de su capacidad para gestionar esta información en vuelo.